At a glance

The Pillar Two global minimum tax is here. Japan and South Korea have enacted domestic Pillar Two legislation, and many other countries, including the UK, Switzerland, Ireland and Germany, have released draft legislation or publicly announced their plans to introduce legislation based on the OECD Model Rules.

Many aspects of Pillar Two will be effective for tax years beginning in January 2024, with certain remaining impacts to be effective in 2025. While each country must enact its own legislation to apply the Pillar Two rules, there is much for multinational businesses to do to prepare for compliance with these rules.

In the US, legislation to enact Pillar Two is unlikely in the near term. But regardless of what the US does (or does not do), US companies with operations in countries that have enacted Pillar Two (1) will be subject to its requirements, including the reporting requirements and, perhaps more importantly (2) they will be at risk of double taxation.

Given the anticipated impact on interim and annual financial reporting in calendar year 2024, as well as future impacts on cash taxes and compliance requirements, companies are encouraged to act now.

Overview

The current international tax landscape has been in place for decades. But now dramatic changes are being made. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), backed by countries around the world, has been pursuing a Two-Pillar Solution aimed at alleviating certain global tax challenges that it believes arose from the “digitalisation of the economy.” This OECD two-pillar framework is significantly altering many current international tax practices with a related impact on reported earnings and cash flows.

In simplest terms, Pillar 1 would change where sales to customers in other jurisdictions are taxed and Pillar Two proposes a global minimum tax assessed for each jurisdiction where a multinational company operates. The ease of describing these pillars belies the complexity of their application and potential impacts.

While the prospects for Pillar 1 remain uncertain, Pillar Two has arrived with the enactment of tax legislation in Japan and South Korea. Additionally, a number of major jurisdictions announced they will enact legislation in 2023, including the UK and Switzerland. European Union (EU) member states are required to adopt Pillar Two into domestic law by December 31, 2023, and accordingly a number of EU member states have recently released draft tax legislation (e.g., Germany, Netherlands).

The OECD’s agenda

OECD comprises 38 member countries (including the US) that collaborate to help set standards for global policies in a number of areas, including tax. In the tax arena, OECD members are joined by 102 additional countries, forming what’s called the Inclusive Framework. Over time, the OECD has increased its focus on mismatches between tax systems of different countries and how multinational enterprises organize their international operations to manage their global tax burden. Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) and country-by-country reporting are OECD-driven initiatives that have influenced changes in tax laws around the world over the last several years. More recently, the OECD has focused on ways to reallocate some taxable profits to jurisdictions where goods are sold and services are consumed, resulting in the proposed Two-Pillar Solution.

The OECD does not have the authority to legislate or implement laws. The goal is for a general consensus among the countries that are represented at the OECD (and the broader Inclusive Framework). From there, each government must implement laws and treaties in order to achieve the agreed-upon objectives. Even though the OECD cannot set laws, the member countries typically agree to revise their own laws to comply with OECD initiatives. Essentially, what the OECD creates as policy today will often drive tax law changes in various jurisdictions.

Pillar Two background

The objective of Pillar Two is for large multinational enterprises to pay a minimum level of tax (a threshold effective tax rate of 15%) on the income arising in each jurisdiction where they operate. This is per the proposal, or “Model Rules,” which are also referred to as the “Anti Global Base Erosion” or “GloBE” rules.

While certain guidance has been released by the OECD (

Model Rules in December 2021, followed by supporting

Commentary in March 2022,

Safe Harbours and Penalty Relief in December 2022, and

Agreed Administrative Guidance in February 2023), additional implementation guidance will be forthcoming. As noted, the OECD cannot legislate local country tax law. Accordingly, while the goal is for enacted legislation to be consistent with OECD guidance, differences among jurisdictions are likely to arise.

Scope of Pillar Two

The GloBE rules would apply to any Constituent Entity that is a member of a multinational group with annual revenue of €750 million or more in the consolidated financial statements of the Ultimate Parent Entity in at least two of the four fiscal years immediately preceding the tested fiscal year.

- Constituent Entity - an entity included in a “Group” that is subject to the GloBE rules (i.e., a multinational enterprise)

- Group - comprises entities (including those that prepare separate financial accounts, such as partnerships or trusts) that are related through ownership or control and generally included in consolidated financial statements of an Ultimate Parent Entity (UPE), including any permanent establishments (i.e., a taxable presence in another taxing jurisdiction) of a Constituent Entity

Certain entities, such as governmental entities and non-profit organizations, are not subject to the GloBE rules.

A Group must include at least one entity or permanent establishment that is not located in the Ultimate Parent Entity’s jurisdiction.

The Model Rules include a de minimis exception. At the election of the multinational enterprise (MNE) Group, there would be no Pillar Two incremental tax (top-up tax) for a Constituent Entity for fiscal years in which:

- the average revenue of such jurisdiction, as defined by the GloBE rules, is less than €10 million; and

- the average income or loss of such jurisdiction, as defined by GloBE rules, is a loss or is less than €1 million.

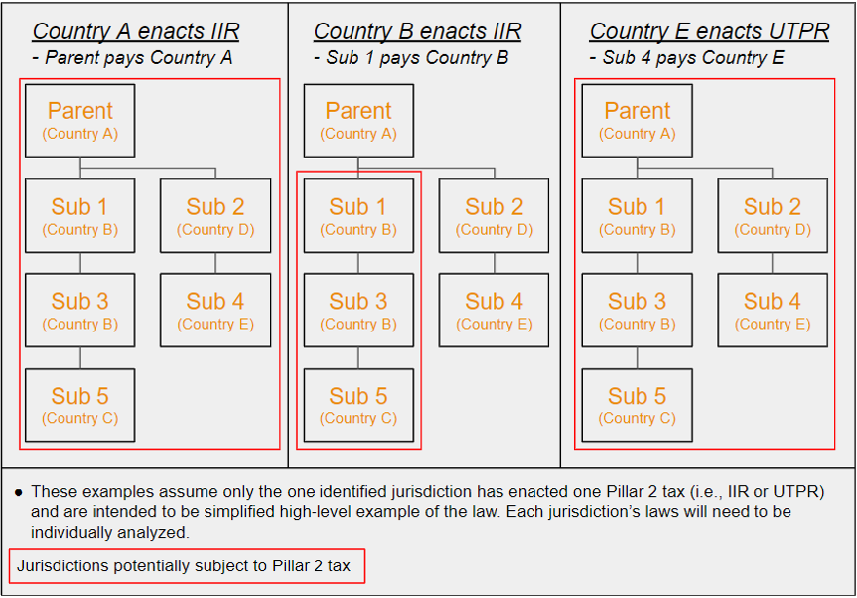

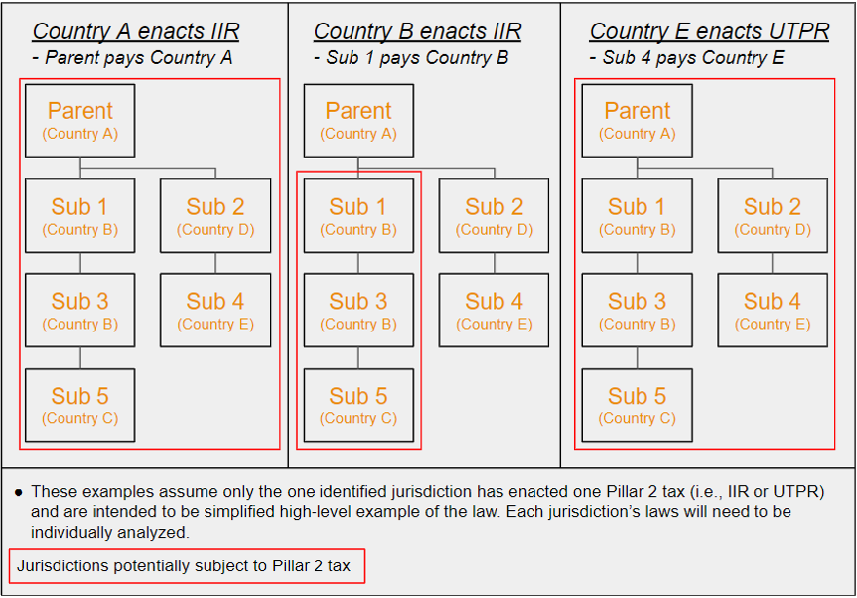

Entity paying the top-up tax

The top-up tax can be administered in several ways, adding to the complexity of this model. While each approach may be calculated using the same methodology, the approaches will differ depending on which jurisdiction collects the tax and the mechanisms by which the tax is collected. Further complicating the calculation, it is generally expected that jurisdictions will enact Pillar Two legislation throughout 2023 to be effective in phases in 2024 and 2025.

Some countries are considering implementing Pillar Two Model Rules to apply to their own domestic income so they can collect and administer the taxes within the jurisdiction where the income is generated (these are referred to as Qualified Domestic Minimum Top-up Taxes or QDMTT).

When a QDMTT does not exist at the local level, if the Ultimate Parent Entity is located in a jurisdiction that has adopted the Pillar Two Model Rules, any required top-up tax on lower tier subsidiaries would generally be collected by the tax jurisdiction of the parent entity, which is addressed in Pillar Two’s Income Inclusion Rule (IIR). If the UPE is located in a jurisdiction where the Pillar Two Model Rules have not been adopted, certain lower-tier subsidiaries can potentially apply the IIR. IIRs are generally anticipated to be effective beginning in 2024.

However, if the Ultimate Parent Entity is not located in a taxing jurisdiction that has adopted the Pillar Two Model Rules (and no other subsidiaries are available to apply the IIR), and no QDMTT is present, then the responsibility for applying the Pillar Two rules may flow to other lower-tier or brother-sister subsidiaries under the Undertaxed Profits Rule (UTPR). In this scenario, for US-headquartered MNE Groups with material domestic operations, it is possible that US earnings could be taxed under this mechanism if the US does not adopt the Pillar Two Model Rules into domestic legislation. UTPRs are generally anticipated to be effective beginning in 2025.

View image

View image

The ability to apply and collect (or otherwise enforce) this tax may vary among the three methods (QDMTT, IIR, or UTPR). Additionally, actual tax legislation enacted in the various jurisdictions will require coordination to minimize double taxation. For US multinationals, this includes consideration of how the existing US Global Intangible Low Taxed Income (GILTI) regime and the recently enacted US “book” minimum tax, which is not considered a Pillar Two equivalent tax regime (despite a similar 15% tax rate and financial reporting tax base), interact with Pillar Two.

Pillar Two - The calculation

Pillar Two taxes are based on book income

Unlike many current tax systems, the Pillar Two minimum tax is determined based on financial reporting results reported in a company’s consolidated financial statements, with certain modifications. This will result in a complex set of calculations that likely require new processes, controls, and systems. Among other considerations, a company will need to maintain separate books and records for each jurisdiction — potentially for each consolidated subsidiary — using the accounting framework of the Group’s parent entity (US GAAP for most US-headquartered companies).

Because the effective tax rate is calculated by jurisdiction, companies will be required to prepare financial reports on a recurring basis at entity levels that previously were likely not necessary. Specifically, items that may be eliminated in consolidation or recorded only in consolidation and not “pushed down” to the individual Constituent Entity’s books and records may affect both the ultimate tax due and the jurisdiction in which such tax is payable. Examples of these items include intercompany sales, intellectual property transfers, management fees, and transfer pricing charges.

Calculating the top-up tax

As proposed in the Model Rules, companies must have a GloBE effective tax rate by jurisdiction of at least 15%. The effective tax rate under Pillar Two (GloBE ETR) is Adjusted Covered Taxes divided by GloBE income or loss.

If the GloBE ETR is less than 15%, a top-up tax would be determined by applying the difference between GloBE ETR and 15% to Pillar Two income less a “substance-based carve out.”

The following illustration demonstrates how the calculation is expected to work for each jurisdiction.

|

|

| |

Calculate GloBE income or loss

| |

| |

Calculate Adjusted Covered Taxes

| |

|

|

Tangible assets plus payroll

| |

Substance-based carve-out

| |

| |

Excess profit (i.e., the tax base for top-up tax)

| |

|

(1)5% used for illustrative purposes. The percentage will vary by year, based upon the Model Rules

GloBE income or loss

GloBE income is defined as earnings under the parent company accounting framework on a separate company basis, adjusted for certain items per the Model Rules. These adjustments to financial statement net income include:

- Net tax expense (generally, current and deferred income taxes);

- Excluded dividends;

- Excluded equity gains or losses (including, but not limited to, certain income or loss from investments accounted for under the equity method);

- Certain revaluation method gains or losses;

- Certain gains or losses from the disposition of assets and liabilities;

- “Asymmetric” foreign currency gains or losses (generally, foreign currency gains and losses that arise due to differences between the functional currency for accounting purposes and the currency used for local tax purposes);

- Policy disallowed expenses (e.g., certain fines or penalties);

- Prior period errors and changes in accounting principles; and

- Accrued pension expense.

In addition to these required adjustments, certain elective measures may be available under the Model Rules. For example, with respect to share-based compensation arrangements, companies may be able to include the local tax deduction in lieu of the share-based compensation expense as determined under the relevant accounting standard. Among other considerations, this election may alleviate the impacts of windfall tax benefits associated with share-based compensation arrangements that could potentially reduce the GloBE ETR calculation below the 15% threshold. Other elections may also be available.

Importantly, GloBE income may be different depending on the accounting framework of the Ultimate Parent Entity. While certain of these differences have been addressed by recent OECD guidance (e.g., differences between US GAAP and IFRS on intercompany transactions), other differences between the applicable accounting standards continue to exist and may impact Pillar Two outcomes.

A practical challenge for companies will be determining financial statement income at the Constituent Entity level. These complications may include the following.

- If Constituent Entity level accounts are maintained using local statutory accounting principles, companies will need to understand all local statutory-to-reporting GAAP adjustments to prepare the Constituent Entity level financials under parent company (i.e., reporting) GAAP.

- Companies will need to determine if any consolidation entries made by the UPE or intermediate holding companies relate to a specific Constituent Entity (e.g., late-arising adjustments) that were not pushed-down to the Constituent Entity’s local ledgers.

- Companies will need to consider the impacts of acquisition accounting entries if such amounts have not been pushed down to local ledgers (and instead reside in a topside or consolidating ledger). Among other considerations, depending on the origin/nature of the original acquisition accounting entries (e.g., non-taxable acquisitions of shares versus taxable asset acquisitions), certain GloBE adjustments may be required.

- Companies will need to understand the consolidation process with respect to the elimination of intercompany transactions, as the separate company financial statements are required to be determined on a pre-elimination arm’s length basis.

Adjusted Covered Taxes

Once the relevant GloBE income is determined, the amount of taxes associated with that GloBE income or loss will be needed to calculate a jurisdictional level ETR. These associated taxes, referred to as “covered taxes,” are broadly defined as taxes imposed on a Constituent Entity’s income, as well as certain taxes that are “functionally equivalent to such income taxes.” The definition of taxes considered to be income taxes under the Model Rules may be broader than those considered to be income taxes under financial reporting standards (e.g., tonnage taxes and tax on corporate equity may be considered). That said, covered taxes do not include taxes such as indirect, payroll, or property taxes, which are not taxes based on income.

Covered taxes are adjusted under the Model Rules before calculating the GloBE ETR. Adjusted Covered Taxes start with current tax expense accrued at the separate company/jurisdictional level, and are then adjusted for a number of items. While not an exhaustive list of all adjustments contained within the Model Rules, the more significant adjustments to current taxes relate to the following:

- Deferred taxes

- Tax impacts associated with uncertain tax positions (until the year in which, and only if, such taxes are ultimately remitted to tax authorities)

- Accrued taxes relating to items of income or loss that are specifically excluded from the GloBE tax base (said another way, if certain taxes were accrued on an item of income that is not included in GloBE income, the associated taxes would generally also be excluded)

- Covered taxes recorded in equity or OCI relating to amounts included in the computation of GloBE income or loss that will be subject to tax under local tax rules

- Any amount of GloBE Loss Deferred Tax Asset (as defined in the Model Rules)

- Qualified refundable and non-qualified refundable tax credits

- Any amount of current tax expense that is not expected to be paid within three years of the last day of the fiscal year (this would reduce covered taxes)

Deferred taxes

The proposed adjustments for deferred taxes received significant attention during the development of the Model Rules. Deferred taxes normally represent the difference between the financial statement basis and tax basis of an asset or liability at the statutory tax rate of the relevant jurisdiction in which that asset or liability will be recovered or settled. They essentially represent the future tax benefit or expense of recovering an existing asset or settling an existing liability at its financial reporting carrying amount. The Model Rules propose to leverage the financial statement deferred tax model to alleviate incremental tax when it is only a matter of differences in timing as to when an item of income or expense is includible in financial statement income versus taxable income. There are, however, two key departures from that financial statement deferred tax model when adjusting a company's current tax for deferred taxes in Pillar Two.

- The deferred tax expense or benefit will be remeasured to 15% if the local statutory rate is above the 15% minimum tax. For example, for financial reporting purposes, deferred taxes in the US would be measured at the federal tax rate plus the applicable state tax rate, which would be in excess of 15%. Therefore, US deferred tax expense or benefit would have to be remeasured for purposes of calculating Adjusted Covered Taxes.

- If a company has recorded a deferred tax expense to establish or increase a deferred tax liability, and that deferred tax liability will not be paid or recovered within five years, then the deferred tax expense related to that liability would not be included in the adjustment to covered taxes until paid or recovered. Application of this rule for tax-deductible goodwill or other indefinite-lived assets such as trade names, when the “deduction event” for book purposes is only upon an impairment or sale, rather than a predictable pattern of amortization, may result in a top-up tax for many multinationals since no deferred tax expense will be included in covered taxes.

– There are several exceptions to this rule. The Model Rules include a list of items for which companies would not need to track the expected timing of reversal. One of the most significant items is fixed assets (for which cost recovery is typically accelerated for tax purposes as compared to the timing of depreciation for financial reporting).

In addition to these adjustments, deferred tax benefits relating to carryovers of non-refundable income tax credits (except certain transition relief afforded under the OECD Administrative Guidance) are also excluded from the Pillar Two covered tax determinations. However, while covered taxes will be higher in the year a carryforward is generated, they will be lower in the year in which the carryforward is utilized.

Qualified refundable tax credits versus other tax credits

With respect to covered taxes, the Model Rules treat qualified refundable tax credits and other tax credits differently, which will have a significant impact on whether a top-up tax is triggered.

Refundable tax credits are generally tax credits that are not dependent on an income tax liability for monetization. For example, certain UK research and development incentives can be monetized against income tax liabilities or other non-income based taxes. In certain jurisdictions, a taxpayer may also receive a direct cash refund even if the taxpayer has no other tax liabilities against which the credit can be applied. For financial statement purposes, refundable tax credits are generally not included within the scope of the income tax accounting guidance. As the monetization of such credits is not dependent on taxable income, such amounts are included in pre-tax income.

Non-refundable income tax credits, on the other hand, are generally reflected on the tax line in the financial statements. The Model Rules similarly generally include the impacts of certain “qualified” refundable credits in GloBE income, as opposed to reducing covered taxes. However, certain “non-qualified” refundable tax credits (generally, credits that are otherwise refundable but are not recovered within four years), as well as other tax credits, generally require further adjustment. Recent US tax legislation in the Inflation Reduction Act has now afforded taxpayers the ability to sell/transfer certain non-refundable income tax credits to other taxpayers. It is currently unclear how such transferable non-refundable credits will be considered under the Pillar Two framework.

Importantly, while a company may receive the same economic benefit of a credit regardless of whether it is refundable or non-refundable (i.e., it would be the same net income in both scenarios), companies that generate non-refundable credits (e.g., US research and development credits) may be significantly disadvantaged under Pillar Two as compared to companies that benefit from qualified refundable credits, given the mechanics of the GloBE ETR calculation.

This is best illustrated by an example.

|

| Refundable tax credit | | Non-refundable tax credit |

|

|

|

|

|

Tax computation - add back refundable credit*

| | | |

|

|

|

Current tax expense (taxable income at 25%)

| | | |

|

|

Effective Tax Rate under US GAAP

| | | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

*Refundable tax credit assumed to be non-taxable in this scenario.

| | | |

|

Other tax credit considerations

Tax equity partnership structures that may generate benefits from tax credits

While the Model Rules generally exclude from GLoBE income equity gains or losses, including certain income or loss from investments accounted for under the equity method, the OECD decided to issue further guidance regarding the treatment of some tax credit investment structures, in part because the financial accounting treatment of these credit investments can differ depending on the structure of the investment and the choices made by the investor. For example, Low Income Housing Credits (LIHTC) are often facilitated through a tax equity structure; however, investors can make an accounting policy choice to account for these investments under the proportional amortization method (PAM) rather than the equity method. Generally, the proportional amortization method results in (1) the tax credit investment being amortized in proportion to the allocation of tax credits and other tax benefits in each period and (2) net presentation of the tax benefits with the amortization of the investment within the income tax line item. The FASB recently issued

ASU 2023-02,

Accounting for Investments in Tax Credit Structures Using the Proportional Amortization Method (a consensus of the Emerging Issues Task Force), which extends the use of PAM to equity investments in tax credit structures other than LIHTC that meet certain criteria. Given the differing accounting treatment of these investments, as well as the importance of providing clarity for the institutions that typically invest in these tax credit structures, the OECD recently issued further clarifying guidance.

The Agreed Administrative Guidance issued in February 2023 sets out a special rule for certain tax credits in the context of equity method investments that provides some relief. The guidance introduces the new concept of Qualified Flow-through Tax Benefits. When an owner is subject to an Equity Method Inclusion Election, it must apply the Qualified Flow-through Tax Benefits guidance with respect to such benefits when they flow through a Qualified Ownership Interest. This special rule is “designed to ensure the neutrality of certain tax equity structures where such non-refundable tax credits are an essential element of the investment return.” The relief appears targeted at tax equity structures whereby a tax credit is an essential component of the expected return on investment. Without this rule, credits earned through equity method investments would understate the GloBE ETR of the Group receiving such credits as compared to a Group that earned a similar cash return. While this aspect of the guidance provides some welcome certainty with respect to select tax equity structures, it falls short of providing an outright exclusion for tax credits derived through investments accounted for under the equity method of accounting. Taxpayers with existing investments in tax equity structures, or plans to invest in them in the future, will need to consider how Pillar Two is enacted as well as whether and how any provided relief may apply in their facts and circumstances.

Investment tax credits

Certain non-refundable income tax credits may be viewed as investment tax credits. Under US GAAP, investment tax credits may be accounted for under the “flow-through” method, in which the associated tax benefits are recognized for financial reporting purposes in the period the credit is generated, or under the “deferral” method. The deferral method allows for the tax benefits associated with the credit to be recognized over the life of the related asset, with the option to present such benefits as a reduction to income tax expense, or in pre-tax earnings. Taxpayers will need to consider the impact of any investment tax credits, including their accounting policy elections, in their Pillar Two calculations. In general, without regard to the accounting policy elections made by a taxpayer, Pillar Two will generally treat tax credits as resulting in a dollar-for-dollar reduction in the taxpayer’s Pillar Two ETR, unless such credits qualify for a specific Pillar Two exception (e.g., the credits are Qualified Refundable Credits or satisfy the criteria for treatment as Qualified Flow-Through Tax Benefits).

Safe harbors - temporary and permanent relief measures

Throughout various public consultation periods on the Pillar Two Model Rules, numerous stakeholders highlighted the need for safe harbors and simplifications to reduce the complexity of performing detailed calculations and meeting potentially burdensome compliance obligations.

In December 2022, the OECD published initial guidance with respect to certain temporary or transitional safe harbors, as well as a framework for development of a permanent safe harbor. The transitional safe harbor guidance may provide for certain jurisdictional relief from the initial application of the Pillar Two rules during the applicable three year transition period. It leverages data from a company’s existing Country-by-Country Reporting (CbCR). Currently, CbCR is required for a significant number of multinational companies, and is typically filed with the parent company’s headquarters jurisdiction (e.g., for US MNE Groups with $850 million or more of revenue in the preceding annual reporting period, such information is lodged with the US federal corporate income tax filing).

Importantly, for a company to utilize CbCR with respect to the transitional safe harbor calculations, underlying data must be derived from “Qualified Financial Statements.” This requires that information contained within the CbCR be developed from the same data used to prepare the consolidated financial statements (or, in certain instances, local statutory financial reporting).

Per the framework included in the OECD’s initial safe harbor guidance, permanent safe harbors will be performed on certain “simplified” calculations, with additional guidance to be released from the OECD at a future date. The simplified calculations will not be based on CbCR information, but rather on the financial reporting data that is required under the Pillar Two Model Rules.

However, if applying the transitional safe harbor guidance, preparing such calculations can present additional challenges beyond the application of the overall Pillar Two Model Rules. Companies will need to ensure that information contained within the CbCR meets the “Qualified Financial Statements” standards. This will likely require companies to consider their existing internal control frameworks over CbCR outcomes, as the determinations can significantly impact a company’s consolidated Pillar Two obligations, and may be subject to additional scrutiny from both external financial statement auditors and various tax authorities.

Accounting for Pillar Two

With all of the complexities in calculating Pillar Two, there is some welcome relief on the accounting for any top-up tax under both US GAAP and IFRS® Accounting Standards.

Under US GAAP, the FASB staff has concluded that the GloBE minimum tax is an alternative minimum tax per

ASC 740,

Income taxes. Based on this conclusion, reporting entities would not recognize or adjust deferred tax assets and liabilities for the estimated future effects of Pillar Two taxes as long as enacted legislation is consistent with the OECD’s GloBE Model Rules and associated commentary. Rather, the tax would be accounted for as a period cost impacting the effective tax rate in the year the GloBE minimum tax obligation arises.

Similarly, while taking a different path, the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) has also concluded that no deferred tax accounting will be required for the GLoBE minimum tax in the near term. In May 2023, the IASB issued amendments to IAS 12, Income Taxes, regarding the Pillar Two Model Rules. The amendments introduce a temporary, but mandatory, exception to the accounting for deferred taxes arising from the implementation of the rules. Additionally, the amendments require disclosures for affected companies.

The amendments to IAS 12 are immediately effective; however, the timing of the required disclosures vary. Further, jurisdictions subject to an endorsement process will need to endorse the amendments.

The guidance statements from the FASB and IASB are welcome in the midst of the uncertainties of Pillar Two. That said, companies subject to Pillar Two will need to include an estimate of any Pillar Two obligations for interim and annual financial reporting periods beginning in 2024.

For more, see our In briefs, FASB staff weighs in on tax accounting for OECD Pillar Two taxes and Global implementation of Pillar Two: narrow-scope amendments to IAS 12.

What’s next?

The proposed rules represent a fundamental change to how companies have been taxed on international operations for decades. The fact that Pillar Two leverages financial reporting income under the accounting principles of the parent company makes preparing for its implementation a cross-functional effort that requires engagement with operational and finance functions well beyond the tax function; early planning and consistent communication will be critical.

While the implementation of Pillar Two-compliant tax legislation in the US is still uncertain, given actions already taken in other jurisdictions, the time to act is now. A common starting point would be to model the impact of the rules on cash taxes and the effective tax rate based upon currently available data. This exercise may identify gaps in the systems (including ERP systems), processes, and related internal controls necessary to collect the data and determine income and covered taxes at a constituent entity / jurisdictional level. Companies should also evaluate the currently available safe-harbor exclusions to assess applicability.

Proactive leadership and substantive preparations now will make the rapidly approaching transition to a new global tax environment much more efficient.

To have a deeper discussion, contact: | | |

|

|

View image

View image