Search within this section

Select a section below and enter your search term, or to search all click Fair value measurements, global edition

Favorited Content

IRR = WACC |

Indicates that the PFI may reflect market participant synergies and the consideration transferred equals the fair value of the acquiree. |

IRR > WACC |

Indicates that the PFI may include entity-specific synergies, the PFI may include an optimistic bias, or the consideration transferred is lower than the fair value of the acquiree (potential bargain purchase). |

IRR < WACC |

Indicates that the PFI may exclude market participant synergies, the PFI may include a conservative bias, the consideration transferred may be greater than the fair value of the acquiree, or the consideration transferred may include payment for entity specific synergies. |

Year |

Revenues |

Net cash flow |

Net cash flow growth (%) |

Actual year |

$95,000 |

$9,500 |

— |

Forecast year 1 |

105,000 |

10,000 |

5.3% |

Forecast year 2 |

115,000 |

11,000 |

10.0% |

Forecast year 3 |

135,000 |

12,500 |

13.6% |

Forecast year 4 |

147,000 |

13,500 |

8.0% |

Forecast year 5 |

160,000 |

14,000 |

3.7% |

TV = |

CF5(1 + g) |

k - g |

TV |

= |

Terminal value |

CF5 |

= |

Year 5 net cash flow |

g |

= |

Long-term sustainable growth rate |

k |

= |

WACC or discount rate |

TV = |

$14,000 (1 + 0.03) |

0.15 – 0.03 |

|

TV = $120,167 |

|

PV of TV 1 = |

$120,167 |

(1 + 0.15) 5 |

|

PV of TV 1 = $59,744 2 |

|

Confirm that cash flows provided by management are consistent with the cash flows used to measure the consideration transferred |

One of the primary purposes of performing the BEV analysis is to evaluate the cash flows that will be used to measure the fair value of assets acquired and liabilities assumed. The projections should also be checked against market forecasts to check their reasonableness. |

Reconcile material differences between the IRR and the WACC |

Understanding the difference between these rates provides valuable information about the economics of the transaction and the motivation behind the transaction. It often will help distinguish between market participant and entity-specific synergies and measure the amount of synergies reflected in the consideration transferred and PFI. It will also help in assessing potential bias in the PFI. If the IRR is greater than the WACC, there may be an optimistic bias in the projections. If the IRR is less than the WACC, the projections may be too conservative. |

Properly consider cash, debt, nonoperating assets and liabilities, contingent consideration, and the impact of NOL or tax amortization benefits in the PFI and in the consideration transferred when calculating the IRR |

Because the IRR equates the PFI with the consideration transferred, it is important to properly reflect all elements of the cash flows and the consideration transferred. Nonoperating assets and liabilities, and financing elements usually do not contribute to the normal operations of the entity. The value of these assets or liabilities should be separately added to or deducted from the value of the business based on cash flows reflected in the PFI in the IRR calculation. If any of these assets or liabilities are part of the consideration transferred (e.g., contingent consideration), then their value should be accounted for in the consideration transferred when calculating the IRR of the transaction. |

Develop the WACC by properly identifying and performing a comparable peer company or market participant analysis |

The WACC should reflect the industry-weighted average return on debt and equity from a market participant’s perspective. Market participants may include financial investors as well as peer companies. |

Use PFI which reflects market participant assumptions instead of entity-specific assumptions |

Entities should test whether PFI is representative of market participant assumptions. |

Use PFI prepared on a cash basis not an accrual basis |

Since the starting point in most valuations is cash flows, the PFI needs to be on a cash basis. If the PFI is on an accrual basis, it must be converted to a cash basis such that the subsequent valuation of assets and liabilities will reflect the accurate timing of cash flows. |

Use PFI that includes the appropriate amount of capital expenditures, depreciation, and working capital required to support the forecasted growth |

This should be tested both in the projection period and in the terminal year. The level of investment must be consistent with the growth during the projection period and the terminal year investment must provide a normalized level of growth. |

Use PFI that includes tax-deductible amortization and/or depreciation expense |

PFI should consider tax deductible amortization and depreciation to correctly allow for the computation of after tax cash flows. PFI that incorrectly uses book amortization and depreciation will result in a mismatch between the post-tax amortization and depreciation expense and the pre-tax amount added back to determine free cash flow. (See FV 7.3.2.1 for further information on calculating free cash flows.) |

Use multiple valuation approaches when possible |

Multiple valuation approaches should be used if sufficient data is available. While an income approach is most frequently used, a market approach using appropriate guideline companies or transactions helps to check the reasonableness of the income approach. |

Finished goods inventory at a retail outlet. For finished goods inventory that is acquired in a business combination, a Level 2 input would be either a price to customers in a retail market or a price to retailers in a wholesale market, adjusted for differences between the condition and location of the inventory item and the comparable (i.e. similar) inventory items so that the fair value measurement reflects the price that would be received in a transaction to sell the inventory to another retailer that would complete the requisite selling efforts. Conceptually, the fair value measurement will be the same, whether adjustments are made to a retail price (downward) or to a wholesale price (upward). Generally, the price that requires the least amount of subjective adjustments should be used for the fair value measurement.

Cash flow payment |

Probability |

Weighted payment |

|

Outcome 1 |

$500 |

85% |

$425 |

Outcome 2 |

250 |

10% |

25 |

Outcome 3 |

0 |

5% |

0

___________

|

Expected cash flow |

$450 |

Product Line 1 |

Probability |

Year 1 |

Year 2 |

Year 3 |

Outcome 1 |

50% |

3,000 |

6,000 |

12,000 |

Outcome 2 |

30% |

8,000 |

14,000 |

20,000 |

Outcome 3 |

20% |

12,000 |

20,000 |

30,000 |

Product Line 1 |

Year 1 |

Year 2 |

Year 3 |

Outcome 1 |

1,500 |

3,000 |

6,000 |

Outcome 2 |

2,400 |

4,200 |

6,000 |

Outcome 3 |

2,400

__________

|

4,000

__________

|

6,000

__________

|

Probability weighted |

6,300 |

11,200 |

18,000 |

Pre-tax profit (5%)1 |

315

__________

|

560

__________

|

900

__________

|

Warranty claim amount |

6,615 |

11,760 |

18,900 |

Discount period2 |

0.5 |

1.5 |

2.5 |

Discount rate3 |

7% |

7% |

7% |

Present value factor4 |

0.9667 |

0.9035 |

0.8444 |

Present value of warranty claims5 |

6,395 |

10,625 |

15,959 |

Estimated fair value6(rounded) |

33,000 |

Outcome |

Revenue level |

Payout |

Probability |

Probability-weighted payout |

1 |

$2000 |

$0 |

10% |

$0 |

2 |

2250 |

0 |

15 |

0 |

3 |

2500 |

0 |

15 |

0 |

4 |

2750 |

50 |

40 |

20 |

5 |

3000 |

50 |

20 |

10 |

Total: |

100% |

$30 |

||

Discount rate 1 |

20% |

|||

Fair value: |

$25 |

A |

B |

C |

||

Revenue forecast ($ millions) |

Probability |

Payment in shares |

Probability weighted number of shares |

|

350 |

30% |

0 |

||

450 |

45% |

0 |

||

>500 |

25% |

2,000,000 |

500,000 |

|

Probability-weighted shares |

500,000 |

|||

Share price1 |

$15/share |

|||

Probability weighted value |

$7,500,000 |

|||

Dividend year 1 (500,000 shares x $0.25/share) |

$125,000 |

|||

Dividend year 2 (500,000 shares x $0.25/share) |

$125,000 |

|||

Present value of dividend cash flow (assuming 15% discount rate)2 |

$203,214 |

|||

Present value of contingent consideration (7,500,000 – 203,214) |

$7,296,786 |

|||

Multi-period excess earnings method including the distributor method |

Customer relationships and enabling technology |

Relief-from-royalty method |

Trade names, brands, and technology assets |

Greenfield method |

Broadcast, gaming and other long-lived government-issued licenses |

With and without method |

Non-compete agreements, customer relationships |

View image

View image

The projected financial information (PFI) represents market participant cash flows and consideration represents fair value |

WACC = IRR |

Alternatively: |

|

The PFI are optimistic or pessimistic, therefore, WACC ≠ IRR |

Adjust cash flows so WACC and IRR are the same |

Consideration is a bargain purchase |

Use WACC |

PFI includes company specific synergies not paid for |

Adjust PFI to reflect market participant synergies and use WACC |

Consideration is not fair value, because it includes company-specific synergies not reflected in PFI |

Use WACC |

Assets |

Fair value |

Percent of total (a) |

After-tax discount rate (b) |

Weighted average discount rates (a) x (b) |

Working capital |

$30 |

7.5% |

4.0% |

0.3% |

Fixed assets |

60 |

15.0 |

8.0 |

1.2 |

Patent |

50 |

12.5 |

12.0 |

1.5 |

Customer relationships |

50 |

12.5 |

13.0 |

1.6 |

Developed technology |

80 |

20.0 |

13.0 |

2.6 |

Goodwill |

130 |

32.5 |

15.0 |

4.9 |

Total |

$400 |

100.0% |

12.1% |

Year 1 |

Year 2 |

Year 3 |

Year 4 |

Year 5 |

|

Revenue |

$10,000 |

$8,500 |

$6,500 |

$3,250 |

$1,000 |

Royalty rate |

5.0% |

5.0% |

5.0% |

5.0% |

5.0% |

Royalty savings |

500 |

425 |

325 |

163 |

50 |

Income tax rate |

40% |

40% |

40% |

40% |

40% |

Less: Income tax expense |

(200) |

(170) |

(130) |

(65) |

(20) |

After-tax royalty savings |

$300 |

$255 |

$195 |

$98 |

$30 |

Discount period 1 |

0.5 |

1.5 |

2.5 |

3.5 |

4.5 |

Discount rate |

15% |

15% |

15% |

15% |

15% |

Present value factor 2 |

0.9325 |

0.8109 |

0.7051 |

0.6131 |

0.5332 |

Present value of royalty savings 3 |

$280 |

$207 |

$137 |

$60 |

$16 |

Sum of present values |

$700 |

||||

Tax amortization benefit 4 |

129 |

||||

Fair value |

$829 |

Categories |

Observations |

|

|

|

|

Use an appropriate valuation methodology for the primary intangible assets

|

The income approach is most commonly used to measure the fair value of primary intangible assets. The market approach is not typically used due to the lack of comparable transactions. The cost approach is generally not appropriate for intangible assets that are deemed to be primarily cash-generating assets, such as technology or customer relationships. As discussed in FV 7.3.4.3, the cost approach is sometimes used to measure the fair value of certain software assets used for internal purposes, an assembled workforce, or assets that are readily replicated or replaced.

|

Value intangible assets separately

|

In most cases, intangible assets should be valued on a stand-alone basis (e.g., trademark, customer relationships, technology). In some instances, the economic life, profitability, and financial risks will be the same for several intangible assets such that they can be combined. See BCG 4.2.2 for further information on the separability criterion.

|

Consider and assess the economic life of an asset

|

For example, the remaining economic life of patented technology should not be based solely on the remaining legal life of the patent because the patented technology may have a much shorter economic life than the legal life of the patent. The life of customer relationships should be determined by reviewing expected customer turnover.

|

Use PFI that reflects market participant assumptions

|

PFI should be representative of market participant assumptions, rather than entity-specific assumptions.

|

Use PFI prepared on a cash basis not an accrual basis

|

Since the starting point in most valuations is cash flows, the PFI needs to be on a cash basis. If the PFI is on an accrual basis, it must be converted to a cash basis such that the subsequent valuation of assets and liabilities will reflect the accurate timing of cash flows.

|

Use PFI that includes the appropriate amount of capital expenditures, depreciation, and working capital required to support the forecasted growth

|

The level of investment in the projection period and in the terminal year should be consistent with the growth during those periods. The terminal period must provide a normalized level of growth.

|

Use PFI that includes tax-deductible amortization and/or depreciation expense

|

PFI should consider tax deductible amortization and depreciation to correctly allow for the computation of after-tax cash flows. PFI that incorrectly uses book amortization and depreciation will result in a mismatch between the post-tax amortization and depreciation expense and the pre-tax amount added back to determine free cash flow. (See FV 7.3.2.1 for further information on calculating free cash flows.)

|

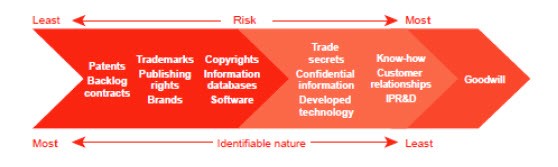

Select discount rates that are within a reasonable range of the WACC and/or IRR

|

In general, low-risk assets should be assigned a lower discount rate than high-risk assets. The required return on goodwill should be highest in comparison to the other assets acquired.

|

Use the MEEM only for the primary intangible asset

|

The MEEM, which is an income approach, is generally used only to measure the fair value of the primary intangible asset. Secondary or less-significant intangible assets are generally measured using an alternate valuation technique (e.g., relief-from royalty, greenfield, or cost approach). The MEEM should not be used to measure the fair value of two intangible assets using a common revenue stream and contributory asset charges because it results in double counting or omitting cash flows from the valuations of the assets.

|

Include the tax amortization benefit when using an income approach

|

As discussed in FV 7.3.4.1, the tax benefits associated with amortizing intangible assets should generally be applied regardless of the tax attributes of the transaction. The tax jurisdiction of the country the asset is domiciled in should drive the tax benefit calculation.

|

Foreign currency cash flows

|

When a discounted cash flow analysis is done in a currency that differs from the currency used in the cash flow projections, the cash flows should be translated using one of the following two methods:

|

Company B net income |

$200 |

Price-to-earnings multiple |

x13 |

Fair value of Company B |

2,600 |

Company B NCI interest |

30% |

Fair value of Company B NCI |

$780 |

PwC. All rights reserved. PwC refers to the US member firm or one of its subsidiaries or affiliates, and may sometimes refer to the PwC network. Each member firm is a separate legal entity. Please see www.pwc.com/structure for further details. This content is for general information purposes only, and should not be used as a substitute for consultation with professional advisors.

Select a section below and enter your search term, or to search all click Fair value measurements, global edition