If a variable interest that is outside the equity investment at risk (e.g., debt interests, management contracts and equity investments that do not qualify as equity at risk) provides the holder of that interest with the power to direct the activities that most significantly impact the potential VIE’s economic performance, then Characteristic 2 may be present and the entity could be considered a VIE.

ASU 2015-02,

Consolidation – Amendments to the Consolidation Analysis changed the evaluation of whether the at-risk equity investors (as a group) lack power when decision making is outsourced through a variable interest that does not qualify as equity at risk. In particular, the changes apply if there is a single decision maker that has a variable interest that is separate from (not embedded in) a substantive at-risk equity investment that conveys the power to direct the entity’s most significant activities. If the interest conveying decision making is not a variable interest, then the group of at-risk equity investors are presumed to have the power to direct the entity’s most significant activities and Characteristic 2 would not be present.

The change in how outsourced activities should be assessed resulted from the FASB’s consideration during the redeliberations of

ASU 2015-02 of whether a registered mutual fund should be a VIE. Prior to the issuance of

ASU 2015-02, a registered mutual fund would have been considered a VIE under the “power” and “economics” version of the VIE model if (1) an outsourced decision maker had power through a variable interest that was not embedded in an at-risk equity investment, and (2) substantive kick-out or participating rights exercisable by a single party did not exist.

The FASB considered the rights exercisable by the shareholders and board of directors of a mutual fund that is registered in accordance with the Investment Company Act of 1940 and determined that these entities should generally be considered voting interest entities. Specifically, the FASB noted that the rights exercisable by a registered mutual fund’s shareholders, either directly or indirectly through the entity’s independent board of directors, are not substantively different from voting rights held by shareholders of a public company (which are generally not VIEs).

The new approach introduced by

ASU 2015-02 shifts the focus from single party kick-out or participating rights to the rights that the entity’s shareholders can exercise in the aggregate. If such rights exist and are substantive, it is presumed that the shareholders can constrain the outsourced decision maker’s level of discretion and decision making authority. Application of this approach may result in the conclusion that the shareholders, rather than the outsourced decisions maker (e.g., manager), have the power to direct an entity’s most significant activities.

Although this concept was discussed in the context of a registered mutual fund, it applies to all entities that outsource decision making through variable interests that do not qualify as equity at risk (e.g., management contracts or equity interests that do not qualify as equity at risk). This approach should not be applied to limited partnerships and similar entities as those entities are subject to the separate requirement described in

ASC 810-10-15-14(b)(1)(ii).

The approach described in

ASC 810-10-15-14(b)(1)(i), which applies to entities that are

not limited partnerships or similar entities, can be summarized in the following three steps.

Step 1: determine if the decision-making fee arrangement is a variable interest

If the decision-making fee arrangement is not a variable interest, then the equity investors as a group do not lack the power to direct the activities of the entity that most significantly impact its economic performance. The nature of that arrangement would indicate that the decision maker is acting in a fiduciary (agent) capacity and is therefore presumed to lack power over the entity’s most significant activities. This is because the decision maker will act in a manner that is primarily for the benefit of the entity’s equity investors. As a result, the entity would not be a VIE under Characteristic 2 and steps two and three would not apply.

Example CG 4-8 illustrates the assessment of the impact of a decision-making fee arrangement that is not a variable interest.

EXAMPLE CG 4-8

Assessing the impact of a decision-making fee arrangement that is not a variable interest

Entity ABC owns and operates data centers in several locations. The data centers house their customers’ servers, provide internet connectivity, and are contractually committed to have the servers operational for 99.97% of the time. Otherwise, Entity ABC would be subject to payment of heavy penalties.

Company A provides maintenance services to Entity ABC that are critical to the data center’s operations. Under the maintenance arrangement, Company A makes all decisions related to the maintenance of the data centers and keeps them operational pursuant to the contractual requirements. Company A has no other interest in the entity.

The maintenance arrangement meets all the conditions in

ASC 810-10-55-37 such that the maintenance fee paid to Company A is not a variable interest (i.e., Company A’s fee is at market, commensurate, and Company A has no other economic interests directly or indirectly through its related parties that are more than insignificant).

What is the impact of Company A’s ability to make decisions through its service provider arrangement?

Analysis

In this example, even though Company A makes critical decisions that have a significant impact on the performance of Entity ABC, the maintenance fee is not a variable interest and Entity ABC would not be a VIE under Characteristic 2. If a decision maker or service provider contract is not a variable interest (see

CG 3.4), then the decision maker or service provider is acting as an agent of the group of holders of equity at risk and would not have the power to direct Entity ABC’s most significant activities.

Step 2: determine if there is a unilateral kick-out or participating right

If the decision-making fee arrangement is a variable interest under the first step, then the reporting entity should consider whether substantive kick-out or participating rights exist. If a substantive right to replace the decision maker or veto (block) all of the entity’s most significant activities exists, then the entity would not be a VIE under Characteristic 2 and step 3 would not apply.

For the purposes of assessing whether a kick-out right or participating rights are substantive when evaluating an entity that is not a limited partnership or similar entity, kick-out rights (which also include liquidation rights) and participating rights should be ignored unless those rights can be exercised by a single party (including its related parties and de facto agents).

Step 3: assess the rights of shareholders

If the decision-making fee is determined to be a variable interest pursuant to

ASC 810-10-55-37, and single party kick-out or participating rights do not exist, then the rights held by the entity’s equity investors must be considered to determine whether the at risk equity investors, as a group, lack the power to direct the entity’s most significant activities. Prior to the issuance of

ASU 2015-02, the group of at risk equity investors was not considered to have power if a decision maker exercised power over the entity’s most significant activities through a variable interest that did not qualify as equity at risk. In such circumstances, the entity was determined to be a VIE under Characteristic 2 unless a single party (including its related parties and de facto agents) could exercise a substantive kick-out or participating right.

ASU 2015-02 introduced a new approach requiring a reporting entity to first consider the rights exercisable by the holders of equity at risk if substantive single party kick-out or participating rights do not exist. This additional step is required only when decision making over an entity’s most significant activities has been conveyed through a variable interest that does not qualify as equity investment at risk and single party kick-out or participating rights do not exist. If the at risk equity investors have certain rights as shareholders of the entity, then the entity would not be a VIE.

ASC 810-10-55-8A provides an example to illustrate the types of rights that may suggest the holders of equity at risk, as a group, have decision making power over the entity’s most significant activities. The example is written in the context of a series mutual fund and points to various shareholder rights as being present, including the ability to remove and replace the board members and the decision maker, and to vote on the decision maker’s compensation. It should also be noted that

ASU 2015-02’s basis for conclusions (BC36) notes that this concept is intended to be applied broadly to all entities other than limited partnerships and similar entities.

Example CG 4-9 illustrates the application of this concept in a non-fund scenario.

EXAMPLE CG 4-9

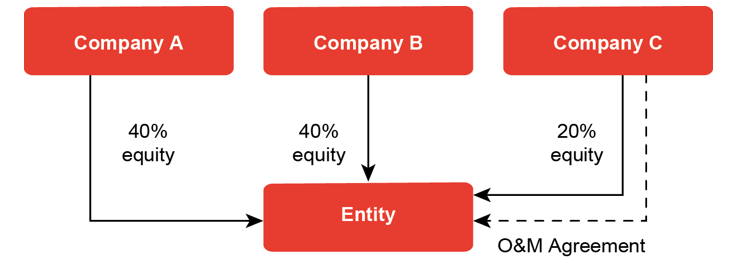

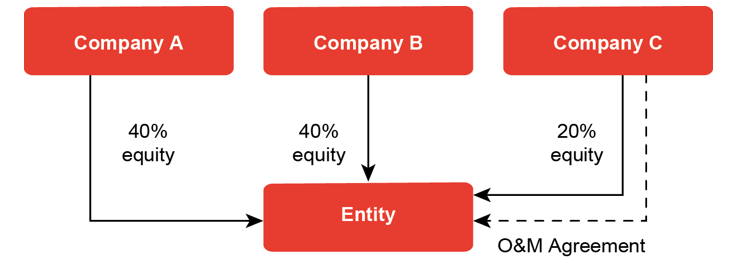

Determining whether rights held by an entity’s shareholders convey power

Three unrelated companies established an entity to invest in shipping vessels. Company A and B each provide 40% of the capital in exchange for equity interests, and Company C also provides capital in exchange for a 20% equity interest. The entity operates subject to the supervision and authority of its board of directors. Each party has the ability to appoint members to serve on the entity’s board and shares in the entity’s profits and losses in proportion to their respective ownership interests.

The purpose, objective, and strategy of the entity is established at inception and agreed upon by its shareholders pursuant to the entity’s formation agreements. The three companies identified and jointly agreed to the specified shipping vessels in which the entity would invest at formation.

Company C performs all of the daily operating and maintenance activities over the shipping vessels pursuant to an Operating and Maintenance (O&M) agreement. The decisions relating to the operation and maintenance of the vessels are determined to be activities of the entity that most significantly impact the entity’s economic performance. Company C receives a fixed annual fee for services provided to the entity that is at market and commensurate. However, the fee arrangement is determined to be a variable interest because Company C has another significant variable interest in the entity (its 20% equity investment).

A number of decisions require simple majority board approval. These include:

- The removal and replacement of the O&M manager, without cause

- Changes in the O&M manager’s compensation

- The acquisition of new ships

- The sale of existing ships

- A merger and/or reorganization of the entity

- The liquidation or dissolution of the entity

- Amendments to the entity’s charter and by-laws

- Increasing the entity’s authorized number of common shares

- Approval of the entity’s periodic operating and capital budgets

View image

View image

Do the holders of equity at risk, as a group, lack the power to direct the entity’s most significant activities (is the entity a VIE under Characteristic 2)?

Analysis

Notwithstanding the fact that the decision-making fee arrangement is a variable interest, the entity would not be considered a VIE. The board is actively involved in making decisions about the activities that most significantly impact the entity’s economic performance. Among other rights, the board is able to remove the O&M manager without cause and approve its compensation. As the board is elected by the shareholders and is acting on their behalf, the shareholders in effect have power to direct the activities that most significantly impact the economic performance of the entity. Accordingly, the entity would not be a VIE under Characteristic 2.

If the board was non-substantive or lacked the legal authority to bind the entity, then the rights exercisable by the board would be less relevant. In that situation, the rights exercisable directly by the holders of equity at risk would determine whether the group lacks power.

Determining which shareholder rights must exist to demonstrate that Characteristic 2 is not present will depend on the relevant facts and circumstances, including the purpose and design of the entity. If an entity has a substantive board of directors, and the board is actively involved in overseeing the business and can legally bind the entity, we believe the at risk equity investors must have the ability to replace the board to demonstrate that they have power unless they have the substantive ability to directly exercise the same rights held by the board.

If an entity is not governed by a board of directors, or is governed by a board of directors that cannot legally bind the entity, then rights exercisable by the board become less relevant to this analysis. In those circumstances, rights exercisable by the shareholders (directly) should be assessed to determine whether they enable the holders of equity at risk, as a group, to constrain the outsourced decision maker’s level of authority and decision making.

Example CG 4-10 illustrates the determination of whether an at risk equity investor has power through an outsourced decision making arrangement.

EXAMPLE CG 4-10

Determining whether an at risk equity investor has power through an outsourced decision making arrangement

Two unrelated parties, Company A and Company B, form a real estate operating joint venture, with each party holding a 50% interest. The venture’s objective is to acquire properties, lease the properties to third party tenants, and sell the properties on an opportunistic basis.

The venture will be governed by a board of directors (the Board), and Company A and Company B will each be entitled to appoint three of the Board’s six directors. The Board will act through a simple majority vote and in the event of a deadlock, a dispute resolution mechanism will take effect to resolve the issue (binding arbitration).

The Board executed a property management agreement with Company B giving Company B the ability to unilaterally direct leasing, maintenance, tenant selection, and remarketing activities related to the properties owned by the venture (the venture’s most significant activities). The agreement has an initial one-year term and will automatically renew for successive one-year periods unless Company B or the Board elect not to renew the contract. In exchange for services provided, Company B will be entitled to an annual management fee and performance incentive fee entitling Company B to 15% of the venture’s profits once the investors achieve a 15% internal rate of return on their capital contributions. Otherwise, Company A and Company B will share in the profits and losses of the venture proportionately.

Notwithstanding the fact that the fee arrangement is at market and commensurate, Company B’s property management agreement is a separate variable interest given Company B’s other significant economic interest (i.e., its 50% equity interest). The decision making rights exercisable by Company B pursuant to the property management agreement were determined to be separate from its 50% equity investment (i.e., they are not embedded).

As shareholders of the venture, Company A and Company B have the ability to make the following decisions through a simple majority vote:

- Terminate the property management agreement

- Approve changes in Company B’s compensation

- Approve a sale of substantially all of the venture’s assets

- Liquidate the venture

- Approve a change in control of the venture

- Approve a change in the name of the venture

- Approve the venture’s accounting firm

As Company B directs the venture’s most significant activities through a variable interest that does not qualify as equity at risk, the shareholder rights exercisable by Company A and Company B must be assessed to determine whether Company B, as property manager, or the group of at risk equity investors have the power to direct the venture’s most significant activities.

Does the venture’s group of at risk equity investors lack the power to direct the activities that most significant impact its economic performance?

Analysis

Yes. Although Company A and Company B have the ability to exercise the rights described above as equity investors of the venture, such rights are not sufficient to demonstrate that the group of at risk equity investors have power. At minimum, the equity at risk must have the ability to remove the property manager, remove the Board (since the Board appears substantive), and approve changes in Company B’s property management agreement, including compensation, to demonstrate that the group has power.

In this fact pattern, Company A and B can each replace their designated Board representatives, and Company A has the ability to withhold its consent to change Company B’s compensation. However, the group’s ability to terminate the property management agreement requires the consent of Company B, the property manager. Because Company B, as an equity investor, has the ability to prevent the group of at risk equity investors from terminating Company B’s property management agreement, this kick-out right is not substantive. Accordingly, rights exercisable by Company A and Company B (as at risk equity investors) are not sufficient to demonstrate that the holders of equity at risk, as a group, have the power to direct the venture’s most significant activities.

If Company A does not have the unilateral, substantive right to kick-out Company B as property manager, liquidate the venture, or exercise participating rights, then Characteristic 2 would be present and the venture would be a VIE under

ASC 810-10-15-14(b)(1)(ii).

The existence of shareholder rights alone is not sufficient to demonstrate that the holders of equity at risk, as a group, have the power to direct the activities of the potential VIE that most significantly impact its economic performance. A reporting entity should also consider whether such rights are substantive.

Determining whether shareholder rights are substantive requires careful consideration of an entity’s governing documents and may also require an understanding of state law in which the potential VIE is domiciled. Consultation with internal or external legal counsel may be prudent in those situations.

The guidance does not specifically state that these rights must be substantive in order to demonstrate that the at risk equity investors have power. However, we believe non-substantive shareholder rights should not drive the reporting entity’s assessment of whether Characteristic 2 is present. We believe the rights exercisable by the holders of equity at risk, as a group, must be substantive to demonstrate that they have the power to direct the activities of the potential VIE that most significantly impact its economic performance.

To be substantive, we believe the group of at risk equity investors must have the ability to exercise such rights implicitly or explicitly. For example, the following may indicate that the rights held by the at risk equity investors are non-substantive:

- The potential VIE is not required to hold an annual meeting

- There is no mechanism for the shareholder group to obtain the identities of the other shareholders and/or convene a general meeting to exercise such rights

- Exercising such rights requires a supermajority vote of the investors as opposed to simple majority vote or lower threshold

- The decision maker holds an equity investment in the entity and can prevent the unrelated at risk equity investors from terminating its decision making arrangement

Figure CG 4-2 includes a decision tree for this characteristic applicable to entities that are not limited partnerships or similar entities:

Figure CG 4-2

Decision tree for Characteristic 2 applicable to entities that are not limited partnerships or similar entities

View image

View image